Books

Prologue

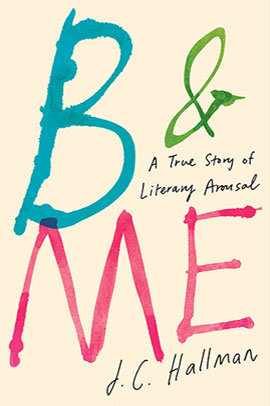

B & Me

Am I becoming a critic? Fine, I don’t mind.

— Nicholson Baker, The Anthologist

What seems odd now, at a remove, is that I fell in love at pretty much the same time I forgot how to love books. Or maybe that makes perfect sense. Several months after my photographer-girlfriend, Catherine, and I seduced each other with sexy letters bridging the three-hundred-mile gap between our homes, she came to join me, packing her belongings into a U-Haul and moving into my dinky apartment in a small city where for the few years previous I had worked toward building a “life of the mind,” reading many books and producing a couple of my own, and to pay the bills working as a “tenure-track” instructor of undergraduate literature and writing.

On the relationship side, this was a glorious time. The transition from our racy scribblings to real life was imperceptible at first, and when Catherine and I weren’t living out epistolary fantasies people stopped us in the street to tell us how happy we looked together. As though we needed to be told! On the book side, however, I experienced a dark turn of mind. This actually began before Catherine hauled her life north, even before we began our portentous correspondence, and it’s probably more accurate to say that a sickly, preexisting blot on my soul had begun to grow. What happened—I think—is that immersion in teaching and publishing exposed me to the literary world’s dark, institutional inner workings, and truth be told even a quick dip into those inner workings would have been enough to trigger a crisis of faith. The exact nature of my dilemma had remained opaque, but it was clear that an essential innocence had been lost.

I got my first glimpse into the nature of this crisis one night a few months into that happy but troubling time, when Catherine and I went to a nearby university to hear James Salter read from his work. Many years before I’d read and greatly admired A Sport and a Pastime, Salter’s homage to sex and France, and Catherine had read the book just recently, and she loved it too, and so while Salter can’t be said to have inaugurated our intimate life—that was sui generis—it is fair to say that he was there right from the start, bobbing in our imaginations as we laid the foundational bricks of our union.

This had as much to do with France as with sex. After graduate school I had almost moved to France – I picked New Jersey instead, a sore point still – and Catherine had lived in Paris any number of times: to this day France is essential to her identity and aesthetic. Neither of us particularly enjoys hearing writers read from their work – far too often the physical presence clashes with the on-page self—but when we heard that James Salter was coming to town we knew we had to go. Because of sex and France, yes, but also because Salter had just recently written a blurb (kind words intended for use in publicity materials) for a book I had edited, an anthology of “creative criticism,” published about a month earlier. It seems obvious now that editing this anthology was among the earliest expressions of my crisis. No one edits anthologies for money, and I had edited mine in a spirit of gasping desperation. Salter’s blurb was auspicious for two reasons: one, because I’d never met him, not once, not even to shake his hand; and two, because he was widely known as a writer who didn’t blurb. Not ever. When you get a blurb from a writer who doesn’t blurb, well, that’s a particular treat, because he or she has selflessly sacrificed a kind of hallowed status. That meant that Salter’s blurb for my anthology really meant something. So of course we had to go to his reading.

Sadly the event was under-attended: sixty or so undergraduates and teachers spread thin through a lecture hall built for three hundred. Salter was unfazed by this. Standing there reading, he was the precise opposite of fazed: a model of calm serenity. I realized that I enjoyed Salter’s on-page and off-page presences equally well. He had had an amazing life, full of adventure and literature and amazing dinners—before the reading began, Catherine and I stopped at the vendor table and bought a copy of Life Is Meals, a book of days Salter had produced with his wife, Kay—and you could see all of it on him: Mustached and dapper, he looked like a seasoned explorer holding court at an adventurers’ club. When he finished reading and the time came to answer a few questions, Salter let the initial awkward silence pass for a moment, and then pivoted theatrically on his feet to present us with a flattering three-quarter portrait of himself. He elbowed the lectern, and huffed a swaggering Dean Martin impersonation into the microphone: “Well – here I am.”

I loved that. I loved that he said that, and for me that was all he needed to be. But other people actually wanted to ask questions. For a time, Salter batted away the usual student queries about influences and work habits, but then he stumbled – and this was the crucial moment of the evening – when a man off to our right stood up and posed a question into a wireless microphone, speaking in an Eastern European accent.

“What is the purpose of literature?”

“What?” Salter said. “What’s the question?”

“What is the purpose – of literature?”

Salter squinted and shook his head, stepped away from the lectern. He cupped a palm by his ear. “What? I can’t – ”

The man was young, dark-haired, thin to the point of emaciation—he might have walked out of Kafka—contrasting in every way Salter’s sturdy, octogenarian vigor. There was some additional back-and-forth, and after the young man repeated his question two or three more times he began to grow embarrassed: Perhaps his English was not as good as he thought. But it was. Everyone in the audience understood the question, and that began to look suspicious. Might Salter’s inability to even hear the question indicate that it was a particularly penetrating question? Could he have been dodging the question, like a politician, because it was the only good question? In any event, the audience wasn’t going to let the miscommunication stand. A couple of helpful people sat up in their seats and repeated the question in raised, insistent voices, and were you to have walked into the lecture hall at just that moment, you might have thought they had an interest in the young man’s cryptic query, that they were converts to his cause.

“What is the purpose of literature?” “What is the purpose—purpose—of literature?”

To be fair, the young man’s accent was fairly thick, and Salter’s ears were probably not what they once were. As well, Salter had been going on for more than an hour by then, and what is sometimes true of reading even enjoyable books—there comes a time when you simply want them to be over—had long since become true of the event. So most people didn’t mind when Salter, having finally grasped the question, flicked it away with the back of his hand and mumbled something about his pay grade.

“You need an expert for a question like that,” he said. And of course he meant a literary critic.

I nearly leaped out of my chair at this. Which was fine, because that was what everyone else was doing, leaping out of their chairs. It was the final question Salter took and it was time to head for the doors. But I was raging inside. An expert? James Salter, you’re the expert! Quite unwittingly, and entirely accidentally, I’m sure—because recall he’d just blurbed my anthology of writers writing about literature, the anthology that had inadequately addressed my blooming crisis—Salter had lent public support to one of the most deeply rooted problems of modern literature, namely that we leave it to scholars to preside over its most vexing question: what it’s for. Catherine, holding my hand, could tell that I’d wandered off into a mental snit. As happy as we were in those days, she knew that some part of me was suffering, and her response so far, and this was simply lovely of her, had been to buy me books. Once, during a visit before she moved in, she left me two books by Roland Barthes on the kitchen table: Roland Barthes by Roland Barthes and A Lover’s Discourse. I needed the latter more than the former, but I read the former right away, immediately incorporating it into something I was working on.

As we got in line to have Salter sign Life Is Meals, Catherine gave my hand a few quick squeezes in that way that newish couples have of communicating understanding during moments of stress. These squeezes offer a wise piece of advice: Hold it together until we’re out of earshot. I was grateful for that. But there was also something Catherine didn’t know. In response to my inward rage, a name reflexively popped into my head, in the way that solutions to puzzles appear suddenly in the mind, that kind of organic unveiling. I thought, Nicholson Baker.

I kept thinking this, over and over—Nicholson Baker, Nicholson Baker—as we edged toward the front of the line. Catherine, my ballast, my rudder, kept squeezing my hand—hold it together, hold it together—and when we finally reached Salter he was incredibly charming, a truly dashing off-page presence. I reminded him about my anthology, which he politely recalled. We handed him Life Is Meals, but before he signed it, in the nick of time, Catherine spotted Salter’s wife a few steps away, and asked her to sign the book as well. I practically burst into tears at this. Catherine had been thoughtful and quick-witted at a moment when, for all practical purposes, I was stunned and thoughtless. And for a moment after that, for just a flash of an instant, the four of us stood there over the now doubly signed book, Catherine and me and the Salters, like friends.